Introduction

The Edwardian era (1901–1910), named after King Edward VII, marked the final breath of aristocratic grandeur before the upheaval of the First World War. In fashion, this brief but influential period was defined by an unmistakable silhouette: the S-shape. Created by corsetry and emphasized through elaborate garments, this new figure—forward-thrusting bosom, cinched waist, and swept-back hips—signaled a departure from Victorian severity and a step toward fluid femininity. Yet beneath its graceful curves, Edwardian fashion carried the weight of gendered expectations, class display, and shifting social tides. This essay explores the meaning and mechanics of the S-shaped silhouette and the culture it adorned.

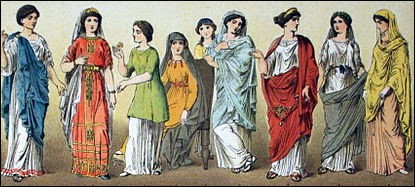

A New Shape for a New Century

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th, women’s fashion underwent a transformation. The hourglass silhouette of the Victorian era—achieved through rigid corsetry and voluminous crinolines—gave way to a curvier, more flowing line. This shift culminated in the S-bend silhouette, also known as the “health corset” shape. Promoted as a more natural posture than Victorian tight-lacing, the S-curve projected the bust forward and the hips back, creating a sinuous, undulating form.

The new figure was achieved through the Edwardian corset, a longer garment that extended over the hips and tilted the pelvis. It reshaped the torso not through extreme compression but through calculated design. The waist was still cinched, but the emphasis had shifted: the female form was no longer compressed vertically, but instead stylized into a flowing line.

The silhouette was complemented by soft, billowing blouses, trumpet skirts, and graceful trains. Day dresses flowed in pastel hues and lightweight fabrics; evening gowns shimmered with lace, silk, and embroidery. Where Victorian fashion had emphasized structure and volume, Edwardian elegance prized movement, delicacy, and grace.

The Gibson Girl: Icon of the Era

At the heart of Edwardian fashion stood the Gibson Girl, a popular illustration by artist Charles Dana Gibson that came to symbolize the ideal woman of the era. With her upswept hair, swan-like neck, and confident poise, the Gibson Girl was fashionable, flirtatious, and fiercely composed. She bicycled, played tennis, and engaged in polite society—all while dressed in the height of Edwardian chic.

The Gibson Girl look required the S-curve figure, a high-necked blouse (often a “shirtwaist”), and a long skirt that flared at the hem. She embodied an ideal of refined independence—a woman who was both elegant and active, modern but respectable. This balance mirrored the paradoxes of Edwardian femininity: women were increasingly visible in public life, yet still bound by strict codes of appearance and conduct.

In fashion terms, the Gibson Girl reflected the rise of ready-to-wear clothing and mass-market beauty. Her image was replicated in magazines, catalogs, and advertisements, making her one of the first truly modern fashion icons. Yet her idealized figure—slim, tall, and corseted—remained unattainable for many.

The Edwardian Corset: Engineering the S-Curve

The Edwardian corset differed significantly from its Victorian predecessor. Rather than lifting and shaping the bust, it flattened the front and pushed the breasts forward, exaggerating the natural curve of the back. This “S-bend” corset typically extended over the hips and ended just below the bust, allowing for decorative bodices and blouses to rest gently over it.

Despite being advertised as a “healthier” alternative to tight-lacing, the S-bend corset was far from benign. It altered posture, tipped the pelvis forward, and restricted movement. Medical professionals and reformers again raised concerns about women’s health and mobility, and the corset became a battleground in debates over women’s rights and bodily autonomy.

Still, the corset was a non-negotiable foundation of high society fashion. Edwardian clothing required it—not only for the desired silhouette but to support the layers of skirts, petticoats, and bodices that defined elite dress.

Daywear and Tea Gowns: Softness and Sophistication

Daytime fashion in the Edwardian era reflected the culture of leisure and display. With the upper classes living in large homes staffed by servants, and the middle classes increasingly embracing genteel lifestyles, the Edwardian wardrobe expanded to include multiple changes of clothing per day.

Tailored walking suits, often made of wool or linen, combined the formality of men’s wear with feminine lines. These suits, paired with wide-brimmed hats and gloves, allowed women to move through public spaces—shopping, promenading, visiting—while remaining impeccably dressed.

In more private or relaxed settings, tea gowns offered a softer silhouette. Loosely fitted and often made from luxurious fabrics like chiffon or silk, tea gowns featured flowing sleeves and minimal boning. They were worn at home during social visits or evening hours and reflected the romantic, almost ethereal aesthetic of the time.

The popularity of such garments reflected an Edwardian emphasis on comfort without compromising elegance. While the silhouette still demanded corsetry, the fabrics and cuts allowed for a sense of movement and airiness.

Evening Glamour and Couture Grandeur

Evening wear during the Edwardian era was a dazzling affair. Gowns were crafted from the finest fabrics—silk satin, velvet, lace—and adorned with beading, sequins, and embroidery. Necklines were typically low, with short or elbow-length sleeves, and trains added drama to every entrance.

The S-shape remained central to eveningwear, with dresses hugging the torso and hips before flaring slightly at the hem. Embellishments emphasized verticality and elegance. Pale pastels, jewel tones, and soft metallics dominated the color palette.

This was also the golden age of haute couture, with designers like Charles Frederick Worth, Jeanne Paquin, and Lucile (Lady Duff Gordon) leading the fashion houses of Paris and London. Wealthy clients attended fittings for custom gowns, while fashion plates and photography spread elite styles to aspiring women across the Western world.

Hairstyles and accessories were essential to the look. Hair was piled high into bouffants or pompadours, often supported by pads or rats. Picture hats, enormous with feathers and flowers, crowned the ensemble. Fans, gloves, and pearl jewelry completed the aesthetic of romantic sophistication.

Fashion, Class, and Display

Edwardian fashion was a clear expression of class identity. Elaborate, impractical garments—especially those requiring multiple changes throughout the day—signaled wealth, leisure, and refinement. The middle class, increasingly upwardly mobile, emulated aristocratic fashion through department stores and sewing patterns.

Working-class women, by contrast, wore simpler versions of Edwardian trends or adapted second-hand clothing. Corsets were still common among laboring women, though less exaggerated. Aprons, smocks, and sensible shoes reflected practicality over display.

Fashion was also used to enforce social roles. Married women were expected to dress modestly and elegantly; younger women could indulge in flirtier styles, but only within limits. A woman’s wardrobe was often her most powerful social tool—projecting her respectability, availability, or ambition without saying a word.

Men’s Fashion: Tradition and Modernity

Men’s fashion in the Edwardian era was characterized by continuity rather than transformation. The standard three-piece suit remained central, though tailoring grew more precise and materials more luxurious. Morning coats, frock coats, and dinner jackets marked distinctions of formality, while bowler hats and top hats denoted status.

New fabrics and construction techniques allowed for slimmer cuts and improved comfort. The Norfolk jacket, often worn for sporting activities, introduced a more casual option for the active gentleman.

Facial hair fell out of favor in the early 1900s, replaced by clean-shaven faces and neat mustaches. Shoes, gloves, and walking canes completed the Edwardian gentleman’s attire, reinforcing ideals of decorum, confidence, and social rank.

Technological Influence and Mass Consumption

The Edwardian period saw major developments in textile technology, retail, and media. The sewing machine and patterned textiles made fashion more accessible, while department stores and mail-order catalogs allowed consumers to participate in trends from home.

Photography and fashion magazines spread images of stylish women and couture collections, bridging the gap between elite and mass-market fashion. The expanding press played a critical role in defining beauty standards and commercializing the Gibson Girl aesthetic.

Additionally, public transportation, like the automobile and electric trams, influenced hemlines and footwear. Fashion had to accommodate the new pace and geography of modern life, especially as women began to enter professions, pursue higher education, and participate in political activism.

The Changing Role of Women

Edwardian fashion existed alongside the growing women’s suffrage movement, the New Woman ideal, and increasing female participation in education and employment. While the fashionable S-curve silhouette emphasized femininity and restraint, women were also demanding greater autonomy in public and private life.

Clothing reforms continued from the Victorian era, with organizations like the Rational Dress Society advocating for looser garments, shorter skirts, and reduced corsetry. While these styles remained marginal, they reflected the broader desire to redefine womanhood beyond decoration and domesticity.

Designers such as Paul Poiret, emerging toward the end of the era, rejected corsetry altogether, offering bold, empire-line dresses that foreshadowed the relaxed silhouettes of the 1910s and 1920s. His influence would help dissolve the S-shape and usher in a new era of fashion freedom.